The exhibition Private Matter? promises a new start for the Műcsarnok, headed by a new curatorial team, who through their choice of artists have made a strong statement about contemporary Hungarian art. There are several aspects of the exhibition which come across as different to the previous practise of Műcsarnok exhibitions, the reduced number of participating artists in the first place, its cross-generational stretch, bold interventions in the exhibition space, ascendancy of relational aesthetics, dematerialisation, and, intentional or not, the sense of sustainability in many works.

The central artworks of the exhibition, Gábor Kerekes’s Tent and Island, reuse postaments from the Műcsarnok storeroom complete with cushions and large flags, successfully creating an environment of a more informal atmosphere, as if the space belonged to the artists and visitors rather than the institution and the exhibition guards. The retro appeal of the work lies in the reference to post-minimalist experiments in gallery „environments” that were common in the early 70s, and the idea of transforming the gallery space into a place for communication, transgression, and social critique.

Although artists from all generations of contemporary Hungarian art are included, arguably it is the younger generation that carries the show with their common interests in collaborative work, concern with ecology and recycling, lightness of touch and desire to communicate, and by placing up-coming artists with the established ones, the specific character of the new tendency appears more starkly.

The purpose-built installation by the Randomroutines is an allegory for the over-production of images, paintings and art objects. A conveyor belt runs uninterruptedly across the floor into a skip, suggesting the fate of creative ideas in the contemporary art world. Visitors are implicated in this process of art consumerism by being forced to trample over the work to pass through the room. The work is carried out in sustainable materials, such as cardboard and plywood, commenting on over-production in society, while the cardboard cut outs in the skip are suggestive of urban guerrillas, and banner like objects in one corner add to the atmosphere of protest in this environment.

Since the early Seventies, feminists have famously proclaimed that the „personal is the political”, and this slogan is very visible in a number of works, and possibly stands for the question mark in the exhibition title. In that sense, it is possible to view the work of Gabriella Csoszó both as a personal photographic diary of artist’s walk along the polluted Danube and as a directly environmental work underlined by the text accompanying the images. Or as one eco-psychologist has it: „How can society be healthy if our river’s are so polluted?”

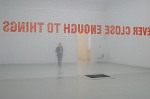

Interestingly related to the previous two works, Emese Benczúr’s monumental sheet of bubble wrap divides a room with the slogan Never Close Enough to Things. Her simple message sets in train philosophical speculations such as: Can art approach the grittiness of reality? Do we expect too much from art objects? Should we be satisfied by art that packages reality and isolates us from the real world?

On the interface of the personal and political is also a work by Szabolcs Kisspál, entitled Shards. Through personal experience and the documentation of a chance encounter with a deer in an overgrown Jewish cemetery in Vienna, his film talks about memory and the ghosts of the tragedy of Kristalnacht.

On the opposite wall is projected Marcell Esterházy’s meditation on the individual experience of time showing his grandfather at family Sunday lunch. Sitting at the head of the table, and eating his soup with great care and enjoyment, the pater familias takes life at a slower pace, seemingly oblivious of the hustle and bustle of the contemporary world. In common with the other films in Private Matter?, it demonstrates a concern with the spontaneous, the unstaged, documentary style, and takes reality as source, rather than fiction, media or intertextuality.

While Anna Fabricius uses staged scenes and obscure fictional scenarios to create attractive images in Temporary Contemporary, György Orbán’s Self-Portrait series is more characteristic of the overall trend: there is no enigma in black and white photographs that, while playful, are presented in the mode of conceptual performance.

The preferred medium of the show is drawing, while painting appears to be the least favoured. The exception is the painter Attila Szűcs, whose peculiar status in the Hungarian art establishment is suggested by the fact that he is the only artist in the show to exhibit oil on canvas. Although it could be argued that drawing is highly personal and immediate, while painting could be perceived as a perhaps more calculated activity, in this show the stress on drawing seems to rely on a formal understanding of dematerialisation.

In that sense, and in reference to the curators’ statement on the precursors of the show, maybe it is the exhibition Poesis curated by Judit Angel a couple of years ago, that inaugurated drawing and personal aesthetics as the new creative maxim in Hungary. On the international scene, the peak of relational aesthetics, as articulated by Nicolas Bourriaud its leading spokesman, was Utopia Station at the Venice Biennale before last. So, from the point of view of international art consumerism, Private Matter? would be labelled as „so 2003”.

More seriously, this show once more confirms the change in contemporary art in the wake of the Nineties. The reasons for this apparent shift can be sought in the post-September 11th world, as it was clearly not just the towers that collapsed. The other turning point could be Michael Landy’s Breakdown of 2001, in which he systematically destroyed all his belongings on the ultimate London shopping street, symbolically destroying the myth of the Young British Artists as well.

In this new approach, where artists take these changes as background knowledge, the need for sustainability, the naturalness of collaborative working, and the desire to ask bigger questions are common traits. These are the notions the exhibition Private Matter? is mediating and this is the way to „get closer to things”.