The selection process of the Hungarian representative of this year’s Venice Biennial has generated intensive debates in the Hungarian art-scene. The jury convoked by the Commissioner (the director of the Kunsthalle) has already announced Csaba Nemes’s project, „Remake” as the winner of the open call when the decision was cancelled adducing a formal defect in the application. The newly announced winner is „Kultur und Freizeit” by Andreas Fogarasi. The procedure has raised numerous questions concerning the functionality of the decision making system, however the projects themselves were overshadowed during the discussions and debates. We’ve intended to stop this gap. (N. E., B. B.)

What do you think of the Venice Biennale?

I think it is a format that is very traditional, could almost be considered a little outdated, but it is still an opportunity for introduction that everyone pays attention to. Great effort can be concentrated on it; all countries usually set aside a larger amount of funding which, indeed, makes the realization of large-scale work possible. For this reason, it is an opportunity that is not to be underestimated.

What is the theme of the work that you entered with and which, as we have found out, you will complete regardless of the results of the competition?

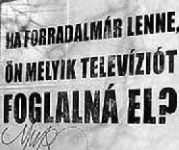

The riots which took place in the autumn comprise the theme of the work. I have chosen the title “Remake” – and my use of the word here is in its more critical sense. What I mean is when an old Hungarian film is remade, our relationship to it is a bit uncomfortable; when you are watching it, it doesn’t seem genuine, but you are curious how this thing works in the present-day context. In general, it usually becomes obvious that it isn’t really applicable. When I watch these autumn events, I experience similarly mixed feelings about it all. In effect, I understand why it has come to this point, but I cannot in the least identify with what happened and I have a hard time defining what it all is – real drama or slapstick comedy, or, more than anything, a reality show that operates through the media, through images, and isn’t necessarily a real event.

How can you still elaborate the topic, then, through what method, being that its interpretation is questionable?

I have thought a lot about what the appropriate format would be and, in the end, I decided on animation because animation is very far removed from the world of technical images – as far removed as possible in fact – but is still moving image composed of drawings and formats reminiscent of drawing. This allows for an approach that is a bit different, the drawn scenes can be a little more general than if we were watching original documentary recordings. For this reason, I think it offers an approach that is a bit different. I would like to create some kind of distance from the events and animation, drawing seem like a good way to do this.

This is the technical aspect. But how can it be made suitable for processing in terms of content; from what vantage point, through what method can such an event be explored in case of an artwork?

It is important for me to avoid political clichés, how events may be perceived from this or that angle. Instead, I would like to use a private vantage point which examines the characteristic that we just talked about: how these happenings looked in the images, and the strange contradictions in the story. This approach is rather ironic or grotesque. Animation should not be understood to mean that these are funny, Tom and Jerry-like characters. What is important is the approach in the drawing; I would say, it shows more of a painter’s perception than that of caricaturist. But it also bares traces of the latter, as we are talking about ten stories here, ten story fragments, short etudes which are usually about a minute long. These include some well known stories, like when the tank starts rolling – a scene that has become known all over the world. But there are also some that I came up with or derived from someone else’s personal account and changed a little.

So the final result is ten one-minute animations which will be projected or shown on monitor.

The films will be projected. Originally, I planned there to be ten separate projections, as the animations don’t have a set order per se. But they can also be sequenced and be presented in a chain. This time, if it all works out, the films will be shown in this latter format in October in the Museum of Kiscell. Initially, we will only make two of them, which will be shown on 19 April at the Knoll Gallery along with the plans for the subsequent segments.

A moment ago you mentioned keeping a distance due to the politicized nature of the matter. How can it simultaneously become distant and personal?

It is not so personal, since I, myself, don’t have personal stories. I was not out there, but I know a lot of people who were or got mixed up in some situation and told me about it. I have seen countless photos on the net and have downloaded videos, which provided my point of departure. I would prefer to say that these stories are of a private nature, which have some personal and some general aspects. This is not a directly political approach of the topic, although it could be that too – it could have a strongly documentaristic vantage point, but that is not my aim.

Why did you decide on the genre of animation, why didn’t you work through the subject by way of the earlier storyboard tradition?

Because the sound aspect of things is very intriguing here and because motion picture allows for a different mode of expression. I am planning scenes where not only gestures but movements too have significance. Storyboards tell a story through images and texts, but they cannot express movements as well as animations can. I will give you an example: here is the well known scene of the tank starting to roll. Index published a photo of this which was probably taken from the window of a flat near Deák Square. On this photo, the tank seems quite toy-like. This is a very opportune viewpoint. This story would be very difficult to relate through the storyboard, but if I start drawing this setup over, it will offer a different approach, which immediately seems a lot more exciting.

You mentioned sound. Are these original sounds or a composition?

Both. We sometimes use original sounds, and even elaborate them, but there are some scenes which are, as I mentioned, invented and elaborated stories that are not part of the existing material and thus have to be shot, so to speak. In many cases, this is how it happens: we prepare a video material, we edit it and then comes the drawing of the story. Here the sounds too are added afterwards. Right now, I have the idea of taking sound in a more abstract direction, that is to say, the technique of dubbing: instead of using the sound that was recorded during the original shooting, mixing the sound afterwards.

You were speaking in the plural before. Do you have work partners or collaborates?

Yes, this is a wholly collaborative project. And one of the great things about it is those few people that I have met in conjunction with it. I would like to mention Éva Magyarósi, an animator and visual artist who is giving me a lot of help on the specialist/technical side, as does Adrián Kupcsik. Then there is also the need for composing music, for example, which I have asked Juci Németh to do, who writes music and lyrics with her friends, Gergely Kovács and Péter Závada. We have further collaborates, such as Film Positive Productions Budapest, who provide us with help in the form of cameraman, production manager and editing.

So this is a larger production with a correspondingly calculated budget.

Yes, calculated, this is where we are now: applying for funding. As of now, we don’t have a penny, the studio offers us its capacity, our colleagues invest their own energy, but of course we are counting on being able to get some funding.

Aren’t you worried about direct political interpretation – that your work will be met with prejudices?

I am sure this will happen to some extent, but I am not worried about it. This is unavoidable, as the topic is a political event, and a very fresh one at that, to which we wanted to react rapidly. So this will obviously happen in some cases. But I think there is room for that, it may even be an exciting thing. I think few artworks in Hungary deal with subject matter that is explicitly political and there are reasons for why this is so.

What are these reasons?

This type of artwork has not met with much success so far – I think this is one of the reasons. Work of this kind has been appreciated neither by the professional scene nor by the public. The other reason is that in the previous era, or political regime, this sort of approach has become, how shall we say, degraded. Artists were happy if they could finally deal with something other than politics. I think all of us felt this to be a delicate area; almost as if the whole thing had turned into a taboo.

What is the reason for the aforementioned unsuccessfulness? Okay, one of the interpretations is that artists were not necessarily seeking political topics, but why could this not be successful on any fronts at all?

I don’t know the answer to this, more people should be asked this question. I only sense that this approach has not been successful. Why that is exactly, I am not sure. I think a view of art has developed in Hungary which thinks more in the long term. We prefer to create work that is solid more in an aesthetical sense; artwork which will retain its qualities and can remain genuine for centuries, or which addresses the audience through various transpositions.

Can you give me specific examples?

Well, if we look at the countries of the Balkans during wartime, or the situation which developed afterwards, a lot of works dealt with very specific things, sometimes even employing sensationalist elements.

Such as?

There is, for example, an artist from Sarajevo – unfortunately I cannot think of his name – who has a piece that is relatively easy to code. He places three photos next to one another: in the first one, he is looks like a first communicant, in the second, he wears a red neck-tie in Tito’s Yugoslavia, in the third, he can be seen with an EU backdrop. These are three self-portraits. So this is a direct, very simply articulated thing.

Do you appear in your own work?

No.

Who do appear in it?

No one specifically, the work does not feature actual characters, so the identity of the participants, in this case, is not important. Obviously, we asked friends to appear in the piece, but during the re-drawing process we will not make the point of rendering their facial features recognisable.

Characters in what sense? What is their position?

Well, that depends. There are different kinds of stories featuring some figures that viewers identify with and some that they don’t, preferring to observe them from the outside. When I say, characters, I mean it is like a study; that, based on the video images, the movements and these figures can be drawn differently. It is important that documentary records have come into existence, which circulate on the worldwide web and through which we see the events that took place – and it is these that we, too, used as our point of departure. The video recordings that we made can be regarded as character and movement studies which complement these records.

Interviewed by Balázs Beöthy

Translated by Zsofia Rudnay