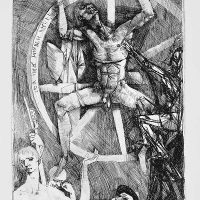

Through the etchings of the Scenes from the Times of György Dózsa series outlines the revolutionary figure of Kondor who is strongly attracted to the portrayal of chaos, revolutions, wars and technical violence. Besides the Angel of Revolution, such works get place in this section that are less known, like the war correspondence Murder at the Olympic Games in 1972, the infernal scene of the Protesting Women and the unique Auschwitz etching.

The prophet Kondor is more known than the revolutionary one who created spectacular and rich illustrations for the works of William Blake and Imre Madách. The prophet had his most significant success as a painter with religious topics and biblical paraphrases. His most famous picture is probably the Municipal Picture Gallery’s panel painting, designed as a fresco, the Marching of the Saints, which was originally to decorate the walls of the Commercial Chamber, is not devoid of irony.

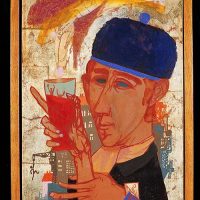

The most often reproduced gold-based, “iconic” painting the Wasp King is similar, pervaded with irony, turning into grotesque. The artist’s “references” can also be found in this section, such as Dürer and the Museum of Fine Arts’ Rembrant and Schongauer etchings as well as pieces by Kondor’s visual and true masters, Jenő Barcsay and Károly Koffán, Sr.

If the revolution section goes round the apocalypse of violence and irrationality then the prophet intensively examines the conflict between saint and profane, sense and emotion and man and woman through such masterpieces as Savonarola or the Saint Peter and a Woman II.

The worker is the figure that is the least often connected to Kondor’s name, however, the majority of his oeuvre was born due to the movement of Socio-reailsm. More precisely, Kondor created his own and peculiar Social Realism that dared to face with topics such as the liberation or the Soviet Republic, but in his technique and topos he revealed the psychic and ideal deep layers of significant topics.

The context of this special artistic attitude of “scientific proletarian” is given by the similar intention works of Tibor Csernus and László Lakner who, similar to Kondor, were experimenting with the deconstruction of Socio-Realism, however, they did not learn their surrealism from Dürer but from Max Ernst.

The biggest question of Kondor’s art is still probably how the spectator can see the real references and the fine criticism of the current system behind and under the surrealism and world of carnival. Beyond this critical reception, it is also worth to pay attention to how Kondor’s masculine and technophile art and his strong worker’s image contribute to his undeniably socialist career.

Sándor Hornyik