Today we’re well aware that “our antiquity is modernism”. An empire disintegrating before our eyes, these modular tower blocks, swing sets designed in the name of progress, concrete park-ing lots on the fringes of the city. The modernist conception for the ordering of everyday life has fallen into ruin. It isn’t a spectacular catastrophe, rather, a slow decline, an ebbing away. Death in installments.

The question is, is this still of any interest to anyone? Contemporary art revolves around a col-lection of similar images from a decent period. And this increasingly resembles a dog chasing its own tail. The modernist utopia has already been over-analyzed from every angle. What’s left?

What would happen if we tried to escape this hackneyed set of associations? To go in search of new metaphors? Freshen up our own lexicon? At least remind ourselves of experiences on a slightly more sensual level, taking our own bodies as our guides, with all their impulses? What would happen if we compared modernist cities to an organism? To plants? To the human or an-imal body?

Withered attempts to answer such questions through the works of Ewa Axelrad, Agnieszka Kalinowska, Kama Sokolnicka and Małgorzata Szymankiewicz – artists who tie in that which is organic with the social. They liken the human body to the collective body. In the sick-nesses of living organisms, animals and plants they see the symptoms of a greater crisis, even a political one.

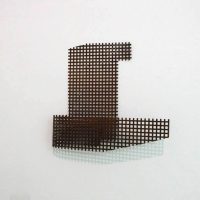

Agnieszka Kalinowska’s Extinguished Neon Signs are objects that have already passed their prime. Once the glittering lights of the city, today extinguished, they have lost their purpose. Kalinowska points to the transience of matter, also to evanescence and the changeability of the ideas that stand behind it. A symbol of the prosperity of old has reverted into a dismal, insignificant skeleton. Kalinowska takes this idea further by making her dead neon signs out of withered plants.

Another work by Kalinowska, made of concrete blocks, cites the realities of late modern-ism: at first glance they appear simply as rough, heavy pieces covered in moss (the “moss” is a green string dotingly arranged by the artist). A closer insight reveals an idea of almost mythic proportions: the remains of civilization swallowed up by the wild. This process can be under-stood as a return to a state of nature – or perhaps conversely, as a sign of civilization’s own as-pects of untamed savagery.

In the films of Ewa Axelrad (made in collaboration with Steve Press) she depicts a city undergo-ing a constant, yet almost imperceptible, change. Ventilators and surveillance cameras melting under bright lights represent a city as an organic beast, living its own life. Throughout these changes there are no signs of any major drama, rather, these are the products of gradual en-tropy. The city is withering away like a dried-up plant.

Kama Sokolnicka’s Locus Solus collage series draws upon Raymond Roussel’s novel of the same title. It’s a characteristic reference, not only because Sokolnicka’s own artistic narrative ties in with a phrase often associated with the literature of Roussel: “stories with cabinets”. In Locus Solus the inventor Martial Canterel invites his friends over to witness a show of miracles he’d created in the garden of a villa outside the city.

Remarkable and strange, these miracles would have satisfied the surrealists of his age. The tale reads as a refined game with the mythology of the garden – this is the trope Sokolnicka trails. Her garden isn’t a metaphor of an orderly world. There is a multitude of meanings to be found, but certainly it is not a garden untouched by the tread of a barbarian. Sokolnicka turns to a similar perspective in a series of three paintings on wood. On the surface these are beautiful, subtle pants. In truth, these are plants copied from the atlas of plant diseases. Here is a garden of illusions, masking death.

The most astonishing of these works may be the painting by Małgorzata Szymankiewicz. A large abstract canvas, painted with a recognizable degree of fluency, is actually an adaptation of a screen shot from a pornographic film. The visuals cue in the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, in-jecting abstraction with erotic overtones, revealing the similarities between plants and the fe-male anatomy.

Szymankiewicz uncovers the body in a moment of crisis, climax – at the moment of orgasm, that “petit mort”. What would happen if we tried to present the contemporary (post) modernist crisis as a post-orgasmic chill? Is the juxtaposition with the enigmatic crux when the body experiences release and a slackening of the limbs after achieving a height of sensory satis-faction not a telling insight into the demise of the modern utopia? Perhaps, at the very least, the entire thing would become slightly easier to grasp? More accessible to the touch?