Since its establishment in 1989, the museum has made it its mission to present and collect the phenomena of Eastern European, American and Western European contemporary art in their entirety, and to gauge the multidirectional and fruitful connections the artists of the region had with post-war international tendencies and art centres. Reinterpreting and recontextualising the pieces on show, the present exhibition endeavours to throw light on the connections we know about or which are yet to be revealed, while reflecting on the social-political changes of the past 50 years and reviewing the history of the museum’s collection.

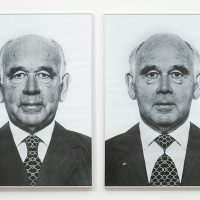

Peter Ludwig, German factory owner and art collector, founder of the Ludwig Foundation and Museum in Budapest, aimed to transcend the Cold War attitude and the rupture between East-West. Already in the 70s, he devoted his attention not only to American art, but also to art behind the Iron Curtain. His taste and methods were often criticised, but his person and his collection both functioned as catalysts in the Budapest scene, resulting in the conception of the first Hungarian museum of contemporary art that would also collect international art.

Launched in 1955, the aim of dOCUMENTA in Kassel was the rehabilitation of modern art in post-war Germany. By now it has evolved into the most important trendsetting contemporary art show in the world. As a special feature of our permanent exhibition, we present István Csákány’s grandiose installation Ghost Keeping (2012), which he created for dOCUMENTA (13). Ludwig Museum is the first venue to display the work after Kassel. István Csákány’s successful participation in Kassel is yet another opportunity for the (Eastern) European situation to become part of the international dialogue.

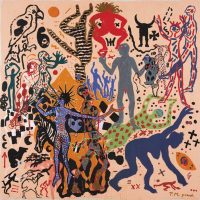

We interpreted Csákány’s theme and radical realism further through some pieces of European new realism, which bear the alienated, surreal or banal mood of twentieth century mass production, the mechanical age. In the iconography of American pop art, this theme is complemented by the symbols and goods of consumer society, the icons of pop culture. The hyperrealism of the 70s pushes this impersonal objectivity to extremes. For Peter Ludwig the collector, the lifestyle and values he could identify with as an industrialist and collector were represented most authentically by the artists of pop art and hyperrealism. Likewise, in the Eastern European tendencies of realism, he valued the representation of reality and people, as he fundamentally considered art a kind of document of the age. He fashioned his collection based on this approach, making the representation of history and people one of its governing concepts.

The European spreading of the American culture and art of the 60s is related to the succession of Venice Biennales and dOCUMENTAs of Kassel. The members of the new generation of Hungarian neo-avant-garde (later Iparterv group) could travel abroad for shorter or longer terms from the early 60s, and this was one of their channels of being informed about international tendencies. The artists who organised the first happening in Hungary in 1966, and who were presented at the so-called “Iparterv” exhibitions of 1968 and 1969 were, for the first time after the war, in sync with current trends; the heterogeneous group was united by the new approach and the need for a collective presence.

The revolutionary mood of 1968-69 brought about the critique of the capitalist system, the reinforcement of leftist ideals in the West. At the same time, the military intervention in Czechoslovakia confirmed that the communist single party system and the Soviet Union would not stand fundamental reforms or social and power realignment. The intellectual members of Western communist parties – Pablo Picasso among them – did not recognise the true face of the Soviet dictatorship. For a long time to come, only controlled and filtered information could pass through official cultural channels.

Several Hungarian artists opted for emigration for political and personal reasons in these years, to create their oeuvres in West Germany, Switzerland, Austria or France. Then again, informal relationships and artistic collaborations were formed between Western and Eastern European artists – around Fluxus events or with the emergence of mail art, among others –, laying the foundations of long-term friendships. An example of this was the Hungarian-Czech-Slovakian art conference of 1971 in a chapel in Balatonboglár, which became the symbolic gesture of reconciliation between the three nations.

The relation between West and East Germany was a particularly delicate subject within the theme of European power games. The subjects of shared German history and contemporary reality were addressed by painters and sculptors pursuing various traditions of realism and expressionism in the two Germanies. Certain German, Hungarian, Russian or American pieces selected from the second half of the 70s and the early 80s also thematise the cold war situation, the communication between East and West and its difficulties, and suggested global solutions that go beyond politics. The elimination of the bipolar world system was eventually brought about by the political changes of 1989; the intellectuals and artists professing the universal principles of artistic individual freedom greatly contributed to the process.

The new permanent exhibition of Ludwig Museum presents about 80 pieces of the collection of more than 500 artworks.