His work began with a radical gesture, when in 1975 he posted an announcement of his own death in a national daily – an act that attracted no attention at the time, and was to radicalize the followers of conceptual art only much later. His first forays into conceptualism were mail art works in the late 1970s, witty pieces that were to shock the addressee (Sample of No Value). The inscriptions of the conceptual works and drawings spontaneously mixed with the hundreds of notes and cards he wrote, the titles and comments that give the impression of self-subsistent pieces, constituting a body of writing that made him one of the preeminent thinkers among Hungarian artists (philosophers of art?).

Érmezei’s whole life took place in various fields of art. At a young age, he was attracted by theatre and he wanted to be a set designer. As a result, he came in association with avant-garde visual artists, among whom Gyula Pauer was to have the greatest influence on him. Pauer helped him to develop the special plaster casting technique whose endless variations he was to use throughout his short but intensive life (Revelation, The Memory of Earth, Corpuses). Cooperation practices are currently of great interest for contemporary art theory; Zoltán Érmezei engaged in a manner of cooperation with János Rauschenberger and Gyula Pauer that is outstanding in Hungarian art history, with the three creating the figure and works of P.É.R.Y. Puci, the mysterious, fictitious female landscapist (By the River Drava). The cycle became an important part of the canon on account not only of the playful idea, but its very topical political reflections as well.

In a variety of forms, cooperation practices were to mark Zoltán Érmezei’s complete career, while he also undertook roles of varying intensity, much in line with international trends. The turn of the 1970s and 1980s saw the dawn of postmodernism, and along with it, that of the New European Painting and the trans-avant-garde. Unselfishly but creatively, Érmezei helped Sándor Altorjai to bring his work in painting to a denouement, lent a hand to Miklós Erdély in his studio, and assisted János Megyik in Vienna to perfect his wooden constructs. It was, however, in the company of János Rauschenberger that he came to conceive and create his most important works, which unmistakeably belonged to the field of sculpture, and later to painting. The Memory of Earth and the other reliefs, these “self-impressions” or “blurred statues” are also very special individual and double portraits, unique in the history of both Hungarian and international sculpture. The distorted forms that were cast can be simultaneously considered caricatural accentuations of emotions, studies in physiognomy, body-art impressions made in the course of actions, and even follow-ups to classical expressionism.

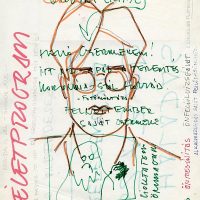

Along with the reliefs, Érmezei made extended drawing series to study his own facial expressions, the changes in his mood and physiognomy. Out of the mirror-situation of the self-portrait grew the most carefully considered examples of cooperation with Rauschenberger, when the two artists painted each other at the same time, while in motion, often on the surface of a mirror. They “fixed the mirror image”, created new mirror paintings, which resulted in not only a new type of image, but a number of instances of verbal play.

Zoltán Érmezei’s whole oeuvre is marked by the masterful use of words and puns, which borders on poetry and philosophy, but which on a more concrete level constitutes unmistakeable reflections on creation itself, the fulfilment of a characteristic of conceptual art, its “metalinguistic” function.

Zoltán Érmezei, who by his own account was working on an oeuvre exhibition throughout his life, bade farewell with an action, a sacral-liturgical rite, at his last exhibition: in 1990, in the Lajos Street exhibition hall of Budapest Gallery he created, with the help of his friends and in the presence of an audience, his own plaster cast, a dramatically executed Corpus, which, when hung on the wall, could not but remind the viewer of the Crucified Christ (or, thanks to Márta Fehér’s video recording of the event, of the Descent from the Cross).

The process of the action was astonishing as the artist’s body was unearthed and assumed the same position as the pseudo-archaeological statues and finds of the Revelation exhibition in the gallery basement, before the ideas of suffering and death, burial and resurrection met in a final spatial and temporal unity. By this time the artist was seriously ill. Strongly reminiscent of a sacred rite or liturgy, the action was a fitting closure to a life’s work that was permeated all along by philosophy and faith.

Several of the works that Ludwig Museum displays at its exhibition of Zoltán Érmezei’s oeuvre have never been seen publicly, or have been in storage for a long time, and are now presented together with their Hungarian context, with such focal points of arrangement as collaboration and the technical innovations introduced to sculpture casting and impression making. The early conceptual, chiefly mail art works, presented now for the first time, throw a new light on the intellectual fermentation of the 1980s, and the connection network of the period’s art scene.

László Beke

Artistic consultant: MMárta Fehér, János Rauschenberger