Diaképről Backlit filmre készült színes digitális nyomat dibondra kasírozva

A művész, a Galerie Loevenbruck, Párizs és a Vintage Galéria, Budapest jóvoltából.

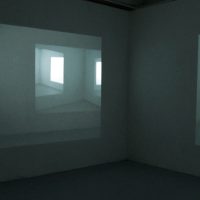

The Colors of Black-and-White, Image A, 2009

Color digital print on backlit film mounted on dibond from eight by ten inch transparency

Courtesy the artist, Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris and Vintage Gallery, Budapest

© Gábor Ősz. A művész jóvoltából / Courtesy of the artist

© Gábor Ősz. A művész jóvoltából / Courtesy of the artist

© Gábor Ősz. A művész jóvoltából / Courtesy of the artist

His beloved picture composing device is the camera obscura or the hole camera, the gist of which is that light gets into a dark cell or box through a tiny hole, and this light draws the upside-down image of the outer world within the camera obscura, on the side opposite the hole. Ősz used this technique in his series entitled Permanent Daylight, where he examines the relationship of artificial light and the built environment.

In the pictures, you can see greenhouses located at the border of Amsterdam, with artificial lights on at night so that the plants can grow constantly. The artist put the camera obscura into a caravan, and created the panorama pictures, showing the inner shape of the caravan, through night-long expositions. The photo series won the price of the 2010 Paris Photo offered by BMW.

The works moving on borderfields of various image making techniques (painting, film, photography) look into such exciting technical and visual questions as the operation of image structure or the tension triggered by the encounter of light and objects.

“What is an image suitable for? What is the image composed of? These two questions are just as important as the one that is most often asked: what is an image? Through years of meticulous research, Gábor Ősz has treated these three problems as parallels and as equally important: in his series, he produces tightly interconnected experimental situations, in which he studies the properties of the image. His experiments basically fall into three larger groups. In his first approach, he builds on both the phenomenon of light and the experience of its perception, for the purpose of examining the concept of the image made of light. The image in this instance is at the same time a sensual impression and a theoretical construction, which can be analysed through philosophical terms, such as ontology and phenomenology. The second experimental approach is linked to the first one by perception and sensual experience. Ősz disassembles the visual phenomenon to find the element most fundamental to his investigations; then he applies changes to this element, just as in a real physical experiment, so that through his interventions, he might reach an ever more precise understanding of the image. He dismantles the concepts of the photograph, in order to get from light to surface-forming pigment, from space to the position of the camera (and back again). In his third approach, he examines first and foremost what portion of reality the photograph might be able to capture, to what extent the image may be used as a narrative tool; what power a picture has to evoke, to cover up, or rewrite a chosen historical context. His visual experiments can just as well be located in a neutral and empty room, as in one of the bunkers of the Atlantic Wall, or in the abandoned site that once had been Hitler’s study. Through Gábor Ősz’s photographic experiments, all the scenes burdened with historical events become bared spaces to be used in his analysis of the image.

At the focus of all three approaches stands the image itself: the problematics of Ősz revolve around the ability of the image to capture and describe the universe, and thus, each of these carefully wrought and exposed pictures aligned in series also addresses the possibility of visualisation. In each of his experiments, he tests the reality-capability of the photograph, while the cornerstones of his investigations are demarcated by general concepts: movement, space and time. How is the still image related to the moving world? How may the photograph, still burdened by countless illusions, and almost regarded as an objective impression of reality, contribute to the moving picture’s completely overriding illusion? Ősz’s photographs are not film-stills: they have no antecedents, they do not combine to form any narrative series, but they are still informed by a filmmaker’s point of view; and the movement in a film is closely dependent on the spatial position of the viewer (the constructed eye) and the viewed (the phenomenon reconstructed in the photograph). Gábor Ősz’s photographs almost invariably build on the simple spatial ambiguity of the basic photographic set-up: the dichotomy of open and closed space. The closed space inside the camera, or the camera obscura, is juxtaposed here with the supposed world outside; the joint packaging of these two spaces reveals illusionistic worlds based on the duality of presence and absence, which in numerous instances is kept in (virtual) movement by the inversion of positive and negative images. The most essential factor in the experimental spaces constructed by the camera – in other words, by the eye – is time. Time, which in the case of Ősz’s pictures, is the basis of all investigations: as exposition time, as the time of the photographer surveying the space, or as historic time. Time, which is carved into the multiple layers of the pictures, but the unfolding of which is in the space of the gallery, through real movement at the exhibition, and becomes most demonstrative before the very eyes of the viewer.

In the early stages of his career, Gábor Ősz painted monochrome paintings – of paintings, among other things. Now, using the devices of photography, he is practically creating abstract spaces far removed from reality, and these photographically bared spaces make it possible for the spectator to meditate on the nature of the image. His photographs require attention and absorption the way monochrome or colour field paintings do. In the at once conceptual and sensual field created as a result of the viewer’s concentration, his works support or deny the possibility of visual perception.”

József Mélyi