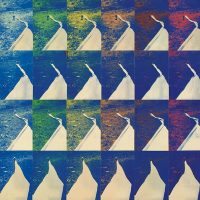

Pécs Workshop: Rolling Stripe, 1975, silkscreen mounted on fibreboard, 320 x 160 cm, courtesy of the King St. Stephen Museum, Székesfehérvár

Pécs Workshop: Light-blue Paper Roll Span in between Trees, November 15, 1970, gelatin silver print, 65.5 x 100 cm, courtesy of the Paksi Képtár

The official cultural scene being centred in the capital, one of the unique characteristics of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde was that it could appear in predominantly rural towns and locations. Meanwhile, keeping closely in touch with artists in Budapest, they contributed to the contemporary scene with such local artistic approaches that operated as almost parallel worlds within the framework of the avant-garde.

The early period of the workshop (1968-70) was characterized by the intention of reviving neo-constructivist art, as well as consciously following the Bauhaus school’s conception of art. In this period they made a number of experiments with material, form and colour, working in different genres (printed graphics, panel painting, etc.) and techniques (enamel and aquarelle among others), deliberately pushing boundaries. By the early seventies, their art exhibited a stronger influence of conceptual art and they began finding their individual voice and set out on the path to becoming autonomous.

They were among the first in Hungarian as well as Central and Eastern European art to carry out landscape experiments in nature and occasionally in urban environments. Throughout 1970-71 their artistic landscape interventions and marks amounted to nearly twenty land art actions (most of them by Károly Kismányoky and Kálmán Szíjártó), which were accompanied by notes and photographic or film documentation. These landscape experiments were unprecedented in Hungarian art history both in terms of their early occurrence and their analytical approach and content.

Further emblematic pieces conceived in the period include Sándor Pinczehelyi’s pictures operating with political symbols (Hammer and Sickle, 1973; Cobblestone, 1974; Star, 1972; etc.), the photo actions and performances by Károly Halász using disembowelled televisions (Private Broadcast, 1970-71; Pseudo Video, 1975) or his miniature museum for home use, lining up miniature copies of the most well-known pieces of contemporary art (Shelves Museum, 1972). Of similar significance are Ferenc Ficzek’s experiments with the medium of photography (e.g. Self-leafing, 1976), or the animations made at the turn of the seventies-eighties (Cube, 1980; Exits Left Behind, 1981).

In addition to chronologically lining up the most significant pieces conceived over the course of the decade, from geometric endeavours, landscape experiments and conceptual pieces through performance documentations and films, the Parallel Avant-garde exhibition also places great emphasis on collecting and presenting contemporaneous archival materials, exhibition catalogues, correspondences and reflexions. In addition, it attempts to explore and reveal the methods of collaboration and collective thinking among the workshop’s members.

The exhibition is also an excellent opportunity to reinterpret the cultural and art policies and processes of the seventies from a new perspective, facilitated by a professional workshop, round table talks, museum pedagogy programs and other collateral events. Additionally, a bilingual catalogue will be published with the purpose of digesting the workshop’s activity and interpreting it in a local and international context. The exhibition will subsequently be presented in Pécs, Szombathely and other regional cultural centres.