Experiencing the human-organic boundaries of the parallel perception of local and universal spatio-temporal relations and processes often gives us new insights. For example, phenomena that are not often perceived may appear on the horizon of consciousness, such as parallelism, relativity, or even the continuous and involuntary loss of data. These realisations certainly make us aware of two things: firstly, they make us aware of the immaturity of our perceptions and, secondly, they reveal something of the immensity of the universe around us and the sublime that it brings.

For Kant, the basic situation for experiencing the sublime is created by the conflict between imagination and reason. The author describes several ways of doing this in his Critique of Judgment. From our point of view, perhaps the third type is the most interesting, most often triggered by the sight of infinite natural phenomena such as the ocean or the starry sky. It is characteristic that in this case the sense of the sublime does not arise from a failure of imagination, but rather from the inertia of the intellect, of the conceptual faculty, and the faculty of cognition and application is significantly inferior to the power of the spectacle. In the meantime, an elemental, intense and poignant mood is created in us, which, according to Edmund Burke, can be associated with pain, terror and solitude.

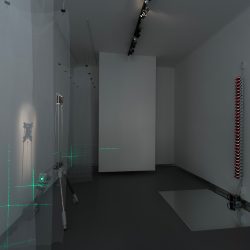

But the sublime is not only evoked by the sight of infinite nature and the cosmos, but also by the visual representation of networks that transcend human imagination and perception. This is the aim of Loránd Szécsényi-Nagy, who is not so much concerned with the manipulation of space as with the possibilities of the relative perception of time in the works presented in this exhibition. The simultaneity of the cosmic or particular series of events represented by the “process gauges” he has assembled are a constant stimulation of our perception. As with Kant, the conflict between imagination and reason is the theme here, with the difference that in Spark, we are not direct observers of the infinite spectacle of nature, but our imagination is held at bay by the relative experience of time produced by the installations.

Ultimately, Szécsényi-Nagy’s works make us aware that the time of the Universe is relative, that is, each observer has his or her own time. The viewer, who is set in and out of a relative system of cosmic and local space-time, is always confronted with the (Lyotardian) question of whether the time he is currently given “happens” in his own imagination or perhaps in his consciousness.